The Trail of Tears

In classrooms across America, the story of the Trail of Tears is often sugarcoated or softened in history textbooks. This sanitization stems from a misguided desire to portray the United States government in a purely positive light.

Such revisionism is more than misleading – it is dangerous. As George Santayana warned, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.” Whitewashing the suffering inflicted by the Trail of Tears makes its injustices easier to forget and risk repeating.

To truly understand this sorrowful chapter, we must face it unflinchingly. This account aims to do just that by peering beyond the platitudes and confronting the stark realities those who walked the Trail endured. Only by reckoning with this painful past can we hope to do better in the future.

The path ahead begins with honesty about where we have been. These truthful lessons of history must not be obscured if our children are to inherit a just world built on empathy and human dignity for all. Though the truth may be uncomfortable, we do a disservice by turning away from it.

Colonialism Arrives in the New World

In the year 1607, a settlement by the name of Jamestown emerged on the shores of the New World. It began humbly, with the English pioneers facing immense challenges in their quest to establish a foothold in this vast and untamed land.

During those early years, the English ventured forth and encountered the indigenous Native Americans who inhabited the surrounding territories. Both parties were undeniably intrigued by the other’s presence, and a natural curiosity led to a mutual exchange of goods, knowledge, and experiences.

The English, like their European successors in the following century, quickly realized the crucial role that the native inhabitants played in their own survival. They diligently studied the Indigenous ways, adopting their methods of hunting and agricultural practices, realizing that these skills were indispensable in this unfamiliar and sometimes hostile environment.

However, it must be acknowledged that the European settlers considered the Native Americans to be primitive, savages simply existing on the fringes of civilization.

The peaceful relations that developed between the two groups were undoubtedly advantageous for the struggling settlement, but the English, along with other European powers, saw colonization as the means by which they could achieve growth and prosperity.

It is important to note that by this time, Europe had already taken root firmly in its own soil. Expansion on the home continent could only come through bloody conflicts and ruthless wars. Yet, the New World beckoned with its promise of vast, untapped resources, offering a more peaceful path to expansion.

Even Queen Elizabeth herself, enchanted by reports of the abundant treasures discovered by her colonists, believed that the Indians surrounding Jamestown would offer little resistance to English expansion. Encouraged by this notion, she fervently advocated for further expansion into the New World.

Now, I’ll spare you the intricate details of the subsequent 100+ years, not out of laziness, but rather because the story remains remarkably consistent. European settlers, driven by an insatiable desire to claim and colonize these lands brimming with wealth and possibilities, became enthralled in the exhilarating race for supremacy in this New World.

The English Settlers Meet the Cherokee Indians

There’s debate about exactly when the English settlers first encountered the Cherokee Indians, but a simple geography lesson tells us that it was inevitable. The original Jamestown settlers had been reinforced by tens of thousands more English who set about expanding the Virginia colony.

Concurrently, the Cherokee Indians had settled throughout the southern end of what would come to be known as the Great Appalachian Valley. So the top of the Cherokee homeland stretched into the western part of what we now call the State of Virginia. With the colonists pushing inland from the east, it was inevitable that the two would meet.

By the time this happened in 1673, the Cherokee had developed some experience trading deerskins to settlers in South Carolina. The Indians needed tools that Europeans crafted from both steel and iron, so it was a friendship of convenience.

The Anglo-Cherokee War

For the most part, Anglo-Cherokee relations were peaceful until the middle of the 18th century. To be sure, it was a period of continued expansion for the colonists, but the Cherokee found it advantageous to ally until British territorial aggressiveness finally shattered the relationship in 1758.

The Anglo-Cherokee war began over a dispute regarding horse theft, but deeper issues of sovereignty and territorial encroachment were at the heart of it. When hostilities ended three years later, there was still a great deal of contention between both sides.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the End of British Colonial Rule

In 1763, King George III used royal proclamation to place a moratorium on the British settlements west of the Appalachian mountains, but it proved nearly impossible to enforce and it did little to repair the damaged relationship.

The Cherokee held on to most of their homeland successfully until the War of Independence officially ended British rule. This was made easier by the general belief that Appalachian land was relatively unattractive from a resource standpoint, not to mention colder in Winter and less attractive for farming.

The Forsaken People – Seeds of Betrayal

Britain’s defeat in the American Revolutionary War was not a positive outcome for Indians. Most tribes, including the Cherokee, had allied with the Crown. There was general consensus that independence would result in even more aggressive expansion.

Not surprisingly, America’s fledgling federal government did very little to quell those fears. It was, after all, a government formed to disperse power rather than consolidate it.

You see, the appetite for land outweighed honor. The peoples were seen as savages, not allies. So the promise of betrayal took root before the echo of muskets fell silent. Fate was sealed as smoke drifted above the council fires.

The Lust for Gold Beckons in Georgia

With the discovery of gold in Georgia in 1829, a land rush developed instantly. Much of where the gold was found happened to be on Cherokee land.

The white men of the area began to immediately look for a way to remove the Native Americans from the land and claim it as their own.

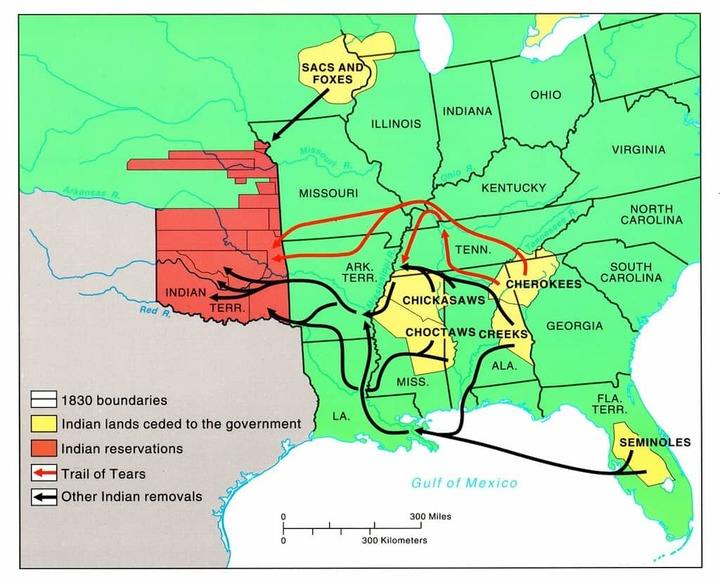

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was the first step toward accomplishing that. Backed by then President Andrew Jackson, it permitted the US government to negotiate with the Native Americans for their land and offer them substitute land west of the Mississippi.

You see, the flash of gold kindled greed in the hearts of men. The Cherokee became obstacles to be removed, not peoples with homes and history.

The cry went up to be rid of them, send soldiers if needed. Honor and promises faded before the lure of riches.

Things came to a head in 1831 when the state of Georgia moved to impose jurisdiction over the Cherokee people. The Cherokee Nation v. State of Georgia brought the problem to national prominence.

In 1833, the Choctaw Nation was forcibly removed and “escorted” by armed guard to western territories. This set a precedent for things to come.

Two years later, the Seminoles defied any attempts at forced removal of their people and started a war that would last for seven years.

Meanwhile, the Cherokee had been under extreme pressure by the state of Georgia to remove from their lands and relocate. This included both state-sanctioned and unsanctioned harassment of the Cherokee people on a regular basis.

Finally, in 1835, weary of their mistreatment by the state of Georgia and hoping to avoid a war like the Seminole and Choctaw were experiencing, the Cherokee signed a treaty that would have them give up their Georgia lands and relocate 2,200 miles away.

You see, the Cherokee clung to hope of honor kept, even as the dark clouds gathered. But always the glare of gold outpaced the light of truth. Their fate was sealed when the promise of peace crumbled to dust, as all promises must when gold is found.

A Journey of Death – Into the Cruel Woods

On May 1838, 7,000 US soldiers entered the Cherokee lands in Georgia and forced the Native Americans from their homes. The men were led to the stockades, arrested while working in the fields for no other crime than being born a Native American.

The women and children were corralled into wagons with whatever belongings they had on them at the time. Very few had blankets with them for the cold and rainy nights ahead. Many were not given time to put on shoes and had to walk barefoot for the length of the journey. Grieving parents were not even given time to bury their dead properly.

These people were torn from their lives like leaves ripped from trees by storm winds. Elders weeping over lost sons marched alongside mothers cradling babes with bleak futures. Even the earth cried out at this wrenching of peoples from lands they had loved.

Under orders from General Winfield Scott, the Cherokee were pushed along the trail at a merciless pace, only stopping when their “escorts” allowed it. Many of the soldiers, 3,000 in fact, were volunteers who sympathized with the natives’ plight.

Some even tried to stop the numerous beatings and mistreatment of the natives along the way. But they were quickly punished by their superiors; even locked in stockades for their show of compassion.

You see, pity flowered in the hearts of some who marched with these exiled peoples. But duty kept their tongues still, as orders barked above the weeping. What honor can be found in such service? Yet still the trail stretched far ahead.

Death was a regular occurrence on the trail, and it wasn’t unusual to lose 20 Cherokee in a single night to pneumonia and mistreatment. Very few of them had ample protection against the elements, so the old and very young tended to die first. Many mothers gave up their blankets for their children, allowing the little ones to make it through the journey when their parents did not.

By November, the procession of soldiers and natives had only reached about halfway to their destination. They were met by terrible sleet and snowstorms that killed off Cherokee by the droves. Those lost were buried in unmarked, shallow graves far from their homes and families.

The trail became a graveyard, mile after mile marked by mounds of rock and earth. Elders and babes surrendered breath side by side in the cold mud. Still the boots and wagons pressed on, chasing the horizon. What waited there but more sorrow?

Arrival in the Unpromised Land

After nearly a year of torment on the Trail of Tears, the remaining Cherokee arrived at their new home in Indian Territory in March 1839. But there was no refuge waiting for them in this harsh and untamed land.

Gazing out over the vast expanse of open prairie, they saw no ready-built houses, no crops planted, no respite from their suffering. Many of the children had lost their parents along the harrowing journey and now faced this bleak future alone.

The struggle to survive would prove even more difficult than the trail they had just endured. With no food provisions and limited means to cultivate the wild lands, hunger and deprivation continued to stalk the refugees.

The remnant found not sanctuary but desolation. Another broken promise in a long line of faith forsworn.

They sank to the cold earth in grief, tears mingling with the blood already shed along the trail. A people bereft of home, bereft of hope.

The Long Shadow of the Trail Where They Cried

In 1835, President Andrew Jackson spoke fine words to Congress, vowing the Indian Removal Act would bring “fair treatment” and “moral improvement” to the Cherokee people.

But you see, those words soon faded, like smoke on the wind when the sky darkened. For the trail that stretched ahead held no justice, only sorrow.

Far from finding promised lands, the exiled Cherokee met only loss. The cold earth swallowed up elders and babes alike along the march. Grief hung heavy over the people like fog, as kinfolk vanished into the wilderness.

Back in their stolen homelands, loved ones lingered in stockades, or hid in the hills like foxes run to ground. Families found themselves scattered like leaves before the storm winds.

The Trail Where They Cried left scars upon the Cherokee as deep and lasting as the ruts made by the wagons that had carried them into exile. Their hearts cried out for missing kin, for the bones left to molder beneath the soil far from home.

President Jackson’s fine words were soon forgot, but the tears shed along that bitter road remain. For promises made by the white man hold little meaning when gold and land stir greed in his breast.

The Trail of Tears stained America’s honor with a permanence; its shadow lingers as a warning of what greed sowed.

Hardship and Healing in the Land of Exile

In the harsh prairie lands, Cherokee leaders toiled to shepherd their bereft people. In 1841 laws were passed to teach the orphaned children, though many had already been claimed by want and illness.

Hunger haunted the exiles, with scarce game or crops to sustain them. They were settlers in a strange land now, far from the stolen graves of their ancestors. The people bowed under hardship, yet toiled to plant new roots.

Slowly, life emerged from loss. Cabins rose beside clear streams, churns filled with cornmeal, drums echoed between hills once more. Children laughed and kicked balls woven of grass, heedless of the haunting past.

Though new shoots grew, the old trees cast long shadows here. An aching distrust of the white man’s promises lingered, prickling like thorns beneath a healing wound. The glowing dream of tilled fields and cabins in this wide land had crumbled to dust.

Still, the Cherokee endured, their voices raised in songs older than memory beneath these foreign skies. Their broken hearts could not forget the Trail Where They Cried, but their hands tended the fragile shoots of renewal. Perchance their children’s children would one day walk in peace again.

Erasing the Voices That Cried Along the Trail

Perhaps the gravest injustice against the Cherokee was the muting of their voices. For when the forced removal was done, the white man’s version alone was heard.

Fine words covered cruel deeds, as the march was recast as a tranquil relocation, not exile at gunpoint. Bold lies obscured harsh truths – the Trail Where They Cried became but a pleasant nature walk.

Shed blood and bitter tears were tidied from the history books, glossed over for gentle readers. The Cherokee voices that rose in weeping chorus along the trail fell silent under the white man’s pen.

This rewriting of events cast long shadows, covering injustices as night covers the wounds of battle. The shared truth lay buried like bones left to bleach beneath an indifferent sun.

You see, lies beget only more evil, as men forget the debts owed to those they have wronged. The silenced voices of the Cherokee echoed unheard down the decades, their muted cries for justice fading like smoke.

But truth can be buried only so long before it claws its way into the light again. The lies told of the Trail Where They Cried must be cast aside. The long path of healing begins in truth, if our people’s hearts can still recognize truth when it comes.